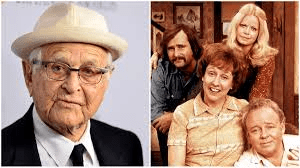

For all the tributes lately paid to the American television producer Norman Lear, who died on December 5 at the age of 101, I still recall the dissenting opinions offered by Mad magazine in its parodies of Lear’s shows All In the Family (“Gall In the Family Fare”) and Maude (“Bawde”) during their 1970s heyday. The first satire, written by Larry Siegel, was introduced, “Now, all of a sudden, a new situation comedy has come along…and it’s entirely different from the old-fashioned family fare. It doesn’t deal with the same old stupid subjects involving idiotic, unbelievable characters. Instead, it concerns itself with relevant, ‘now’ subjects, involving even more idiotic unbelievable characters!” And “Bawde,” written by Tom Koch, featured the title figure regaling some Girl Guides with references to the Gay Liberation Party, the Universal Abortion Party, and the Pro-Porno Party: “You brats just gave me a chance to boost our Nielsen rating by shocking twenty million people three times in one sentence!” Bawde exults.

As usual, Mad cut through the hype. The “realism” of Lear’s sitcoms may have contrasted with the ridiculous premises of Hogan’s Heroes, Gilligan’s Island, and The Beverly Hillbillies, or the implausibly wholesome domesticity of The Brady Bunch and The Partridge Family. But Archie Bunker, Maude, J.J. Walker, George Jefferson, Fred Sanford and Ann Romano were themselves caricatures only a little more like ordinary people than the wacky POWs of Stalag 13 or the laugh-tracked castaways of the SS Minnow. Across his lineup, Lear’s formula was to drop contemporary political, racial, or sexual controversies into standard half-hour plotlines and call it significance; the number of actual families weekly living through scenarios of rapes, abortions, ethnic conflict, screaming fights and noisily flushing toilets was likely a lot smaller than the population of his TV universe. It was, by then, further manifestation of a predictable cycle – just as the genuinely groundbreaking music and attitudes of the 1960s counterculture were reduced to the corporate contrivance of The Monkees, so were serious matters of class, diversity and morality reduced to the prime-time yuks of One Day At a Time or The Jeffersons.

Though Norman Lear is justly admired for his commitment to free speech (he founded the People For the American Way anti-censorship lobby in 1981), he also came to personify the stereotype of the disingenuous Hollywood liberal, churning out provocative but profitable content and wrapping himself in the flag of artistic expression, or “breaking taboos,” while climbing to the top of the showbiz aristocracy. In 1982 Lear showcased a melting-pot patriotism in his ABC special I Love Liberty, of which critic Mark Crispin Miller reflected, “Lear’s ‘America’ recalled that variegated and good-natured herd which we see in ads for Pepsi, Coke, Dr. Pepper, Replay gum, etc. – a mass of happy shoppers, apparently defined by superficial differences, but fundamentally united in their urge to purchase things no more distinctive than themselves.” His sitcoms were broken up by commercial breaks, keeping sponsors happy by keeping spectators glued to the set awaiting the next scandalous zinger. Maybe Lear’s characters and stories were what television needed in a tumultuous time – or maybe it was just offensiveness for its own opportunistic sake, the broadcast equivalent of clickbait that prefigured the outrage-as-entertainment sensibility dominating the entire media landscape today.

From this perspective, Lear was really a pioneer of the “normalization” that modern conservatives denounce: he took valid but essentially marginal issues – the growth of single-parent homes, say, or the emergence of a Black middle class – and gave them a platform disproportionate to their measurable presence in society. Yes, sometimes that meant TV watchers got to see people who looked like themselves on the small screen, but sometimes that meant TV watchers saw people who bore no relation to anyone they knew, yet had to assume were really out there, because the small screen was always said to be a window on the world. The result was to exaggerate the public visibility of otherwise small demographics, like reactionary hard-hats or cantankerous junk dealers, which in turn inspired audiences to feel that they too should act and think the way Archie Bunker or Fred Sanford did. Meanwhile, those who didn’t recognize Lear’s creations in their own neighbors or relatives might well have felt such figures were being artificially foisted on them by powerful industry moguls with private agendas: the sitcom as social engineering.

This chicken-or-egg conundrum applies to all art and literature (does fiction reflect truth, or the other way around?), but the problem was especially acute given the vast viewership of network television in the 1970s and 1980s. Lear may have claimed that his programs were merely depicting charged social topics already roiling mainstream American life, but perhaps he was the one nudging those topics to extra prominence, exploiting trendy themes that occupied radical-chic types by representing them in the telegenic language that held the attention of average consumers. As someone once said, nobody ever went broke underestimating public taste. Countless situation comedies, dramas, and reality shows have since copied Lear’s schtick, seizing some or other hitherto private embarrassment or fringe concern and promoting it as a disease of the week, Very Special Episode, or Must-See TV. In the long run, it wasn’t good for the country, but as Bawde noted, it was good for ratings.