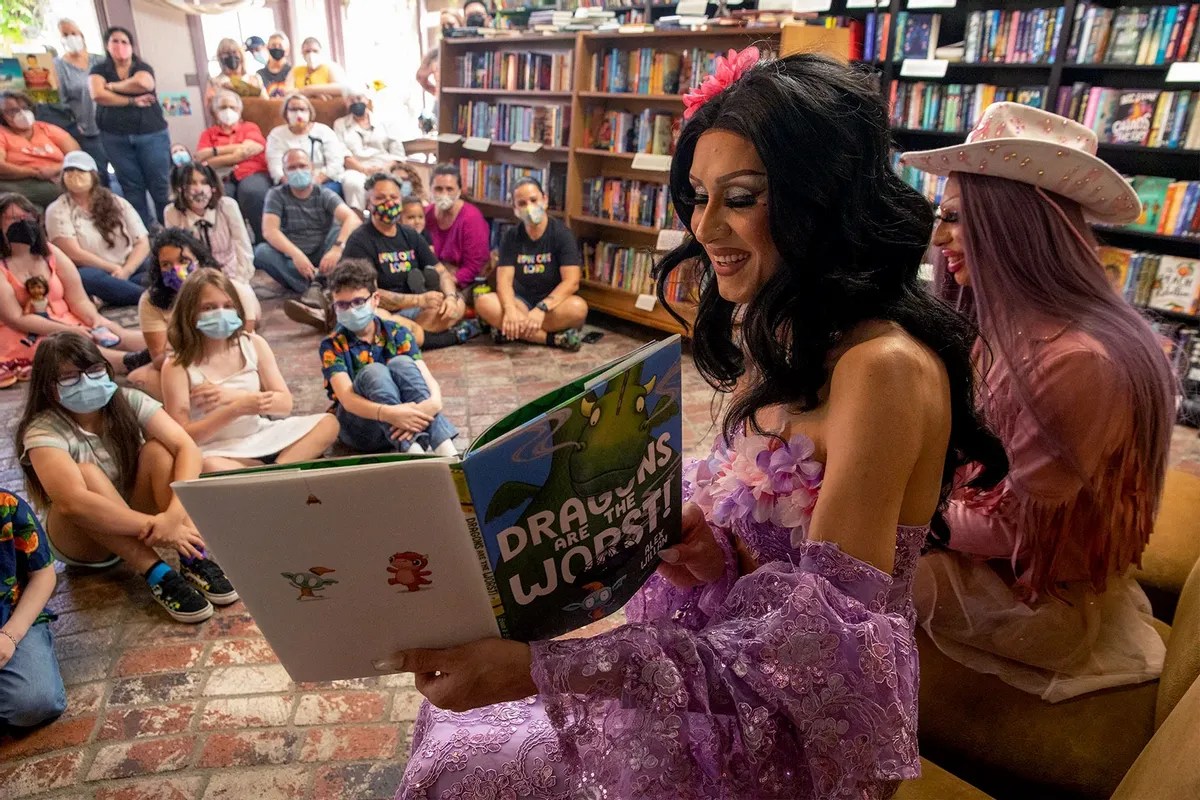

Another day, another protest against drag events. Across numerous jurisdictions in Canada and the US, news reports now regularly tell of demonstrators picketing or disrupting schools and libraries where drag artists have scheduled readings to children. In St. Catharines, Ontario, the public library’s Drag Queen Story Time was interrupted by a handful of angry objectors; in Owen Sound, more than one hundred people rallied to denounce a drag reading at the small Ontario town’s library; a community center in New York City’s Greenwich Village where a drag storytelling was to take place was the scene of “far right” displays in opposition; similar disturbances occurred at a drag story hour in Petaluma California; the gazetteer of anti-drag occasions expands. Yet given the broad familiarity of homosexuality, the widespread acceptance of gay marriage, the celebrity of gay and transgender individuals in many fields, and even the universal availability of every conceivable type of erotic picture and pornographic video, why have drag performances, of all things, become controversial?

To be fair, social scientists now cite a long list of historical practices around sex and gender that differ from the ones we’ve been used to. Intimate male relationships were unremarkable in ancient Greece and Rome. Female roles in Shakespeare’s plays were originally acted by men. Court eunuchs and castrati singers served Asian and European royalty. Indigenous Americans acknowledged “two-spirit” members of their tribes. Only by the Victorian era and the infamous 1895 trial of Oscar Wilde did the official prohibition of sodomy, i.e. homosexuality, diffuse outward into a wider cultural rejection of same-sex desire and what would today be called gender fluidity.

And even then, those rules were often subverted. The bobbed-hair, hard-partying flapper type of the 1920s was considered a violation of feminine norms: “In 1840 women were required to faint to show their delicacy,” wrote the Jazz Age chronicler F. Scott Fitzgerald; “in 1924, women are required to dissipate to show their sportsmanship.” The cabarets of Weimar Germany staged their own upsets of male and female style codes. During this tumultuous epoch, observed Modris Ecksteins in his 1989 cultural analysis Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age, “For the first time in history, breasts were looked upon as a blemish and the brassiere became a flattener rather than a booster. The natural shape of the waist was eliminated…Buttocks, too, disappeared.” Later, Katherine Hepburn’s scandalous slacks and Marlene Dietrich’s top hat and tails were further breaks with convention.

Another wave of gender-bending swept through the 1960s and 70s. The long men’s hair popularized by the Beatles was at first seen as “girlish,” and countless ordinary young guys were harassed for their supposedly effeminate coifs. In 1969’s Easy Rider, counterculture heroes Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Jack Nicholson portrayed the hippies’ common encounter with rural rednecks – “They got some fancy bikes out there, that’s some Yankee queers,” an onlooker snarls – and Bob Seger’s 1976 road anthem “Turn the Page” recounted the derogatory whispers overheard by hirsute touring musicians in a restaurant: All the same old clichés, Is that a woman or a man? Other pop songs, like the Kinks’ kinky “Lola” (1970) and Lou Reed’s “Take a Walk on the Wild Side” (1972) pushed the boundaries of sexual ambiguity, as did the confessed or hinted orientations of glam and shock rockers like David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Elton John, and Freddie Mercury.

Over the same era, the spectacle of men wearing women’s clothes was usually played for giggles. The classic 1959 comedy Some Like It Hot contrasted Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon’s awkward disguises as members of an all-girl band with the genuine sexiness of Marilyn Monroe’s Sugar Kane. Comedians Milton Berle, Benny Hill, and the Monty Python troupe built many of their skits around themselves looking silly in wigs, dresses, and makeup, and the character of Klinger (Jamie Farr) on the long-running TV series M*A*S*H repeated the same gag in multiple episodes, an obviously straight man donning elaborate women’s outfits in order to disqualify himself from military service. Cue the laugh track. Klinger’s ploy was the entire premise of the American sitcom Bosom Buddies (1980-82), starring a young Tom Hanks. The movies Tootsie and Victor/Victoria (both 1982) took only slightly subtler perspectives, and as late as Tim Burton’s 1994 biographical film Ed Wood, the titular Z-grade director’s private penchant for skirts and angora sweaters made for surreal humor when acted by Johnny Depp.

At some point, however – post-Stonewall but pre-AIDS – the gay community began to claim this image as something more than a cheap joke. Homosexuality had been removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders in 1973, and the clinical terminology of transvestitism and cross-dressing were likewise fading into obsolescence. Gay men who once amused heterosexual nightclubbers by appearing the accoutrements of glamorous dames made the gig empowering rather than degrading, especially when they did the same acts for sympathetic houses of LGBTQ folks or appreciative friends (Australian comic Barry Humphries’ Dame Edna character was a key step in this direction). The trend gathered momentum, and in the same way that the word “queer” went from an insult to a positive label, by the time RuPaul’s Drag Race debuted on television in 2009, drag performance had taken on an activist edge: once judged at best a decadent quirk and at worst a criminal perversion, the shtick was now being offered as mainstream entertainment, and a noble cause.

But then someone had the brainstorm that a form of theater hitherto associated with a sophisticated, highly specialized adult subculture was just the thing needed to promote children’s literacy. And it was here that the backlash began. After all, although much of the tolerance that LGBTQ people had accrued in society and under the law derived from the ain’t-nobody’s-business ideals of free association and free thought granted to autonomous men and women, the tolerance was reserved for grownups. For all the increased openness afforded to discourse around sexuality that had arisen since the 1960s – ranging from practical information about birth control, pleasure, and sexual health, to explicit depictions of the act itself – preadolescents generally remained excluded from the conversation, and the milder suggestiveness of M*A*S*H or Monty Python was still reserved for prime time, not Saturday mornings.

Even after the sexual revolution, governments kept legal ages of consent on their books, and long hushed-up experiences of sexual molestation of kids by adult authorities (relatives, teachers, coaches, priests) at last began to be addressed, with victims assured of their blamelessness and perpetrators assured of their punishment. More, consensual liaisons between adults of disparate ages, like a middle-aged professor and a young student (or a president and a White House intern), are now perceived as problematic. Differences in power, maturity, and status remain red flags on the sexual landscape. Drag story times, in which drag performers recite picture books to preschoolers and seven-year-olds, mark a conspicuous exception to these standards.

Some of the disconnect lies in the oddly retro nature of drag itself. In the typical household or workplace of the Twenty-First Century, males and females might wear nearly identical pants, shirts, coats, and hairstyles, to say nothing of the unisex outfits worn by doctors, airline pilots, and military personnel. The rigid sartorial demarcation between genders that prevailed in 1935 went out with Easy Rider and “Turn the Page.” A time traveler from the Jazz Age might conclude everyone in 2025 is an androgyne. Drag presentation, on the other hand, relies on exaggerated fantasies of femininity – heavy cosmetics, gaudy jewelry, high-heeled shoes, low-cut gowns, lush tresses – that the contemporary bus driver, office clerk, or single mom has no time for. Drag is not about average dudes dressing like average women, but about a small cohort’s obscure tastes in old-time fashions and campy nostalgia: harmless, perhaps, but hardly a civil right to be celebrated. We’ve spent generations telling little girls that they too can grow up to be athletes, police officers, and businesspeople, and teaching little boys that it’s all right to cry. Drag acts play up the very sex stereotypes we discourage elsewhere.

Even gay and lesbian men and women have been at pains to demonstrate that they are just like anybody else, aside from the intimacies they cultivate in their personal lives. Who can object to that? The cruel caricatures of the flamboyant queen or the mincing neurotic should be well behind us by now, yet drag exhibition, whether in front of children or not, reinforces the reputation of LGBTQ people as outrageous characters defined by their predilections for glitzy costumes and affected personas. It’s a reversal perfectly captured in the 2001 headline from the satirical news site The Onion: “Gay Pride Parade Sets Mainstream Acceptance of Gays Back 50 Years.”

Granted, there are places where you can enjoy watching fetishized paradigms of maleness and femaleness that you’ll never see on the street. They’re called “strip bars” and they cater to straight men and women stimulated by the sight of real breasts and derrieres barely covered by lacy lingerie, or muscled torsos accessorized only by a bow tie. Anyone under eighteen is denied entry. Yet somehow drag story hours have bypassed the barriers imposed on burlesque shows and Chippendales revues. You probably wouldn’t hire Dita von Teese or Magic Mike to help your child learn the alphabet, but hiring a drag performer who plies an adaptation of the same visual formulas is apparently okay. The difference is that the former appeal to an unprotected class of oppressors, and the latter is held to be a member of a vulnerable minority.

And here we come to the real “agenda” of drag story times. So accustomed are we to the rhetoric of inclusion that we continue to invoke it when virtually no one remains excluded. Politicized out of all proportion to any lingering disadvantages, the defiant motif of Pride has by now been supplanted by the proselytizing impetus of Cool. Drag readings, taking place in a climate that’s already accommodated working mothers, stay-at-home dads, gay politicians, rainbow flags and gender-specifying email signatures, are part of that drift. Although the events are pitched as a matter of fundamental equalities, they don’t represent a freedom to be defended so much as a style to be sold. They are not directly recruiting youngsters into a gay identity for future exploitation (their opponents’ paranoia to the contrary), yet they are indeed advertising relatively rare and certainly complex human traits to impressionable minds better left to discover them on their own.

Think of it this way. There’s nothing inherently immoral about quaffing a few beers after work every evening, or betting on pro sports, or sleeping with serial partners, or bidding for World War II military items online. But there’d be something weird about inviting the drinker, the gambler, the swinger, or the collector of Luger pistols to talk about their hobbies in a Kindergarten classroom. If you want to do any of those, fine, but save the self-promotion – or the self-justification – for a more discriminating crowd. Similarly, drag story times burnish a marginal, almost compulsive form of behavior with the secondhand innocence of the setting and the listeners, serving more to flatter the conscience of the performers than to heighten the awareness of the attendees.

Introducing drag acts to juveniles also distorts the spectrum of opportunities awaiting children as they grow up, by privileging one real but fringe inclination over a hundred more plausible interests (baker, astronaut, writer, hockey player, veterinarian, cowboy, cowgirl, etc.) that might be nurtured by supportive families from an early age. A parent may make peace with their adult child’s eventual decision to act as a drag artist. They’re more likely to resist, however, when their first-grader declares an ambition to be a drag artist after they’ve seen one welcomed into the school library.

To paraphrase a well-known slogan, they’re here, they’re queer, and we’ve all gotten used to it. The drag story times that arouse such ire in Petaluma, Owen Sound, and all points in between, may just be a failed final stretch of a movement that’s otherwise been pretty successful. It’s a success better consolidated than flaunted. “In the gay rights movement, there had always been an unspoken golden rule: Leave the children out of it,” the gay commentator Andrew Sullivan recently explained in a New York Times essay, “How the Gay Rights Movement Radicalized, and Lost Its Way.” “We knew very well that any overreach there could provoke the most ancient blood libel against us: that we groom and abuse kids…So what did the gender revolutionaries go and do? They focused almost entirely on children and minors.” For protesters, the point is not to roll back anyone’s gains, but for everyone to recognize how much has been gained up to now, and to question whether the only unrealized dream haunting this particular sect of emancipated adults can really be to preach their sermons before such unformed, uncomprehending captive audiences.