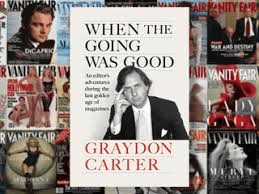

Vanity Fair magazine is still relevant. A piece by Chris Whipple in its December 2025 issue quoted Susie Wiles, Chief of Staff in the Donald Trump White House, and her candid revelations of Trump’s character (the POTUS has “an alcoholic’s personality,” she said) and other inside dirt (veep J.D. Vance has been “a conspiracy theorist for a decade”; Russell Vought of Project 2025 is “a right-wing absolute zealot”) made international news. The publication has previously scooped stories exposing the identity of Watergate’s “Deep Throat” informant in 2005 and the gender transition of Caitlyn (nee Bruce) Jenner in 2015, among various other scandals and sensations which originated in its glossy pages. Not bad for a publication first retailed between 1913 and 1936 and then revived in 1981. Now Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair’s editor from 1992 to 2017, recalls his own eventful time at the prestigious magazine in When the Going Was Good. He’s written an entertaining memoir of an era, but he’s also confessed, unintentionally, his responsibility for the era’s aftermath.

Certainly Carter is aware that things have changed since his editorial tenure. Crammed with gossipy anecdotes and revealing cameos, many of his recollections in When the Going Was Good begin with “In those days…” or “Back then…” The indiscriminate litter of dropped names include heavyweight writers Christopher Hitchens, Nick Tosches, Sebastien Junger, and Dominick Dunne, star portraitist Annie Liebovitz, outlaw filmmaker Roman Polanski, disgraced Harrod’s head Mohamed al-Fayed, legendary producer Robert Evans, and Vogue empress Anna Wintour, along with Monica Lewinsky, Gore Vidal, Princess Margaret, Harvey Weinstein, Larry David, Tom Cruise, Richard Gere, and Carter’s Vanity Fair predecessor Tina Brown. Beneath its topical backgrounds of the OJ Simpson trial, the Iraq War, and annual Oscar parties, the setting of the book is a pre-internet lost world of journalism and business, offering a marvelous glimpse into the mechanics of producing high-end consumer magazines in the last decades of print’s primacy.

Carter’s Millennial readers may be surprised to learn how editorial and marketing staff once all worked out of the same bricks-and-mortar offices; how Vanity Fair’s big-name contributors were provided with generous advances and leisurely deadlines for turning in their manuscripts; how big-name photographers and designers were courted and indulged as much as any temperamental reporter; how full-time teams of copy editors and fact-checkers were vital to the preparation of the monthly finished product; how bruised egos and thwarted ambitions among the masthead glitterati were inflamed and mollified; how the all-important ad revenue was sought and contracted (a full-page spot in one issue of VF might cost fashion or cosmetics houses more than $100 000). Did you know that popular journals were once issued in paper and physically distributed to retail outlets called “newsstands”? The reminiscences in When the Going Was Good will confirm the parallel trajectories which others have charted of Esquire, Rolling Stone, the New Yorker, Sports Illustrated, and Playboy magazines: they don’t make ‘em like that anymore.

It helps, too, that When the Going Was Good is co-written with James Fox, a British novelist who also collaborated on Keith Richards’s 2010 autobiography Life – Fox imparts a similarly natural voice to each man’s story, taking them from modest origins (Graydon Carter grew up in the sleepy Canadian capital of Ottawa and spent a youthful summer literally working on the Canadian National Railway) to immersion in the lifestyles of the rich and famous. A mere ghostwriter wouldn’t have made these journeys convincing. Carter and Fox recount a hilarious episode from the editor’s early stint writing for Time, when a Canadian idiom for idleness was mistaken by sophisticated New Yorkers for an admission to bestiality; elsewhere Carter’s 1986 breakthrough creating Spy magazine is retold in the same slickly catty tone perfected by its subject: “We assumed that many of the younger members of the staff, who would gather at bars in the neighborhood after work, were seeing each other in a manner that can only be described as nonprofessional…It was never great to find yourself in the pages of Spy. But it was worse never to be mentioned.”

Yet as fun as Carter’s career highlights are, even the most appreciative audiences won’t help noticing that When the Going Was Good often comes across as an uncritical travel guide to that most fallen of empires, the bicoastal media elite. It’s a culture that’s all but collapsed under the combined effects of smart phones, social networking, and political populism, but Carter scarcely acknowledges them: “You only realize it was a golden age when it’s done. And the magazine business, brutalized not just by the great recession of 2008 but also by the relentless appetite of the internet, was in the beginning of a period of rapid decline.” True enough, but he’s got nothing to say about the ordinary citizens directly affected by economic disruption, and how further and further removed they became from the celebrity moguls and aristocrats who were profiled in – and who were largely responsible for – Vanity Fair.

In this sense, Carter’s generally fond account of his work history might serve as an unwitting Exhibit A for the most embittered right-wing, left-wing, and even anti-Semitic conspiracy theorists who’ve emerged in the years since he left his VF post. His giddy stories of hobnobbing with an exclusive set of very rich and very connected insiders, collectively wielding an outsize influence on popular styles and public policy, seem to pull back the curtain on a closed community whose existence millions have long suspected but never delineated in such lavish detail as Carter furnishes here: a cozy club of financiers, fashionistas, and Hollywood agents, all dining, drinking, feuding and sleeping with each other while they fund each other’s expensive projects and validate each other’s expensive tastes, in a flattering, soft-focus version of the same dynamic which angrier chroniclers have portrayed as a pigsty of decadent millionaires, spoiled heiresses, and top-hatted capitalists. Even his glitzy backdrops of chic eateries and red carpets in Manhattan, the Hamptons, Soho, Beverly Hills, and Cannes will confirm the resentful paranoia of downsized QAnon followers from Oklahoma or the English Midlands.

Carter does admit that a 2002 VF article on Jeffrey Epstein made no mention of impropriety with underage girls (Epstein was then a private citizen protected by strict libel laws), and that Spy‘s relentless teasing of a certain “short-fingered vulgarian” New York real estate striver helped goad him into an unlikely bid for the US presidency – “Donald Trump is not a man who is easy to ignore. But I assure you, it’s well worth the effort.” There’s no doubt that Carter and his A-list friends were genuinely smart, talented, and industrious, that their larger-than-life ambitions were rewarded with worldwide fame and fortune, and that VF has been a high-quality publication for a long time. But without really meaning to, When the Going Was Good also makes it clear how much the breathtaking insularity of the magazine’s contributors and subjects has come back to haunt them, and all of us.