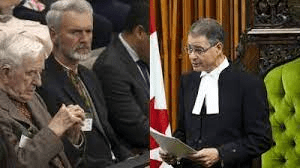

Someone should give Anthony Rota a history lesson. He’s the Member of Parliament for North Bay Ontario, and up until recently Speaker of the House of Commons, who last week introduced his constituent, 98-year-old Yaroslav Hunka, as a “Ukrainian-Canadian war veteran” and a “Canadian hero,” in the Parliamentary gallery during a state visit from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. He was duly applauded by other MPs at the time, but it soon emerged that Hunka actually served with a volunteer Ukrainian unit under German command on the Eastern Front during World War II – in fact part of the infamous SS. It’s become a significant embarrassment for Justin Trudeau’s beleaguered government: Rota was forced to resign on September 26, and there are now calls for the elderly Hunka to be extradited to Poland.

Apparently no one got the message that fighting for the Ukraine against a Russian invasion was a lot different in 1943 than 2023. When the German military launched its assault across Soviet-occupied Poland and the western USSR in 1941, they were at first welcomed by Ukrainians as liberators from the hated regime of Joseph Stalin, whose policies had already resulted in the deaths of millions during the state-organized famines of the 1930s. As in other countries the Germans took over, including Denmark, the Netherlands, and France, some Ukrainian locals were willingly recruited into the Nazi war machine, out of genuine support for Hitler’s ideology (including its vicious anti-Semitism), a desire to be on what then looked like the winning team, or just a mix of adventurousness, opportunism, and a lesser-of-two-evils preference over Soviet Communism. Yaroslav Hunka was probably one of hundreds of thousands of young men in Eastern Europe for whom the enemy of his enemy was a friend. Yet Canadian politicians have fallen over themselves in rushing to condemn Anthony Rota for bringing “a Nazi” into Parliament.

There’s certainly no evidence that Hunka committed any war crimes while in uniform, that he was a card-carrying National Socialist, or that he even did any actual fighting against anyone. But such is the terror among public officials of appearing to inadequately deplore the Holocaust that this hapless old man – and his Parliamentary representative, who must have assumed that any and all historic defenders of Ukrainian autonomy are present-day good guys – have been rapidly given the torch-and-pitchfork treatment. To add to the sense of selective outrage, just think of the shifting attitudes towards Russia that we in the West have had to adopt over the last hundred years: radical experiment (1923), bloody dictatorship (1937), glorious ally (1943), Red menace (1953), rival superpower (1973), Evil Empire (1983), hopeful democracy (1995), failing kleptocracy (2010), and imperialist aggressor (as of this month). During the Cold War, idealistic left-leaners who’d gone to fight in the Spanish Civil War against the Hitler- and Mussolini-backed forces of Francisco Franco were in trouble for being “premature anti-Fascists,” since they had once indirectly helped Stalin; in our era, Yaroslav Hunka is in trouble for being a premature anti-Russian, since he’d once indirectly helped Hitler. He was on the right side, just at the wrong time. This chaos of approved and prohibited allegiances recalls Big Brother’s sinister indoctrination in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia…”

In his 2010 book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, TImothy Snyder described the almost unimaginable horrors visited upon Poland, the Ukraine, and their environs across some fifteen years, while the Twentieth Century’s two most brutal totalitarian powers rolled back and forth over them. Aside from the Biblical tally of combat casualties between 1939 and 1945, the dead civilians numbered about 14 million: gassed in extermination camps, shot in mass pogroms, starved on farms, executed in prisons, and otherwise murdered in the name of racial and political fanaticisms we can scarcely comprehend. Stable and prosperous modern Canada, in contrast, is home to both a proud Jewish community and a significant Ukrainian diaspora, where memorials to victims of the Holocaust and the Ukrainian Holodomor stand – some might say compete – in many places. Unfortunately, the way these real legacies are balanced against contemporary standards of diplomacy, justice, and politics means that sometimes a well-meaning acknowledgement of one gets cast as an unforgivable affront to another. Anthony Rota isn’t the only Canadian who needs a history lesson.