With the movie industry increasingly vulnerable to new media and new tastes, Hollywood is increasingly dependent on the financial security represented by intellectual property, or IP. IP is the catalogue of pre-existing, pre-sold stories and characters which can be profitably adapted into film: sequels, prequels, re-boots, and “re-imaginings,” as well as franchises based on popular novels and comic book series, and new instalments in the continued exploits of familiar figures like James Bond, Bridget Jones, and the Equalizer. But one form of IP that producers are heavily leaning on of late is the musical biography.

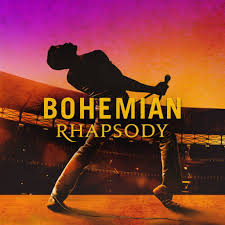

In the last twenty years or so, we’ve seen many famous musicians’ lives and art depicted on screen, including Ray Charles (Ray, 2004), Johnny Cash (Walk the Line, 2005), James Brown (Get On Up, 2014), Brian Wilson (Love and Mercy, 2014), NWA (Straight Outta Compton, 2015), Elton John (Rocketman, 2019), Mötley Crüe (The Dirt, 2019), Queen (Bohemian Rhapsody, 2018), Elvis Presley, (Elvis, 2022), Leonard Bernstein (Maestro, 2023), Bob Marley (One Love, 2024), and Bob Dylan (A Complete Unknown, 2024), and there are upcoming projects on Bruce Springsteen and even a reported quadrilogy on the Beatles; no doubt various spec scripts and development deals about many other big names are also floating around. Nothing succeeds like success, and capitalizing on the proven successes of legendary R&B, rock, country, reggae, rap and classical stars has become a vital business strategy in a business apparently starved for original ideas.

Or maybe it’s the public that’s lost its appetite. Music biopics have the advantage of attracting both casual listeners who already know the songs but haven’t learned much about the backstage drama (and thus will forgive omissions or inaccuracies in the retelling), as well as hardcore fans who feel obligated to watch out of loyalty. As much relevance as the cinematic medium has lost in the age of Tiktok and Youtube, there’s still a lingering sense that being immortalized in a movie confirms the subject’s lasting significance – although, for what it’s worth, I can recall my Vancouver worksite being briefly taken over for the production of 2000’s Take Me Home: The John Denver Story.

A corollary of this belief, however, is that movies like Bohemian Rhapsody, co-produced by surviving Queen members Brian May and Roger Taylor, are made and presented more like deluxe merchandise for completists rather than stand-alone portrayals which anyone can appreciate. You’ve bought the original albums, you’ve got the posters, the T-shirts, and the DVDs, now here’s the officially sanctioned dramatic film to round out your collection. As it is, putting popular copyrighted songs in any movie can take up a big part of the studio budget, but when the artists are still alive and licensing rights to the music are closely controlled, it may be nearly impossible to make a biopic that isn’t somehow approved by the artists themselves, or their estate. There’s a Jimi Hendrix movie from 2000, Hendrix, that obviously couldn’t get permission to show the guitarist playing his own tunes, so you don’t hear the essential “Purple Haze” or “Little Wing,” but at least Jimi is seen wailing through his covers of “Wild Thing,” “Hey Joe,” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Meanwhile, even the sordid sex and drug misadventures highlighted in The Dirt are no doubt as Mötley Crüe wanted us to see them, in exchange for playing actual Mötley Crüe tracks and generally promoting Mötley Crüe’s overall product line.

What’s strange, too, is that virtually every popular musician since the advent of movies and television has already been captured for posterity in miles of performance footage as well as countless still photos. You’d think that seeing the same people played by actors under often awkward makeup and wigs wouldn’t have much appeal – why watch Timothée Chalamet in A Complete Unknown when you can watch the real Bob Dylan in Don’t Look Back and Eat the Document, or in assorted Youtube videos and concert documentaries? – but maybe younger viewers just don’t care. To them, perhaps, Dylan (or Elton John or Bob Marley) might as well be Napoleon or Beethoven: historical figures so remote that they can only be understood through a modern idiom, recreated by modern players for modern audiences.

In the future this paradox may be resolved by interspersing contemporary shots of actual musicians in authentic performance with AI-generated versions of their private, unrecorded lives, enabled by anonymous stand-ins and voice performers. Since most biopics rely on lip-synching and instrumental miming to act the music anyway, it’s a short technological leap from there to using nothing but archival images, as well as archival sounds, to tell the entire story; the CGI-heavy Bohemian Rhapsody especially looks like it was made in a computer rather than on sets. In any case, I dread the day when Chuck Berry or Led Zeppelin are reduced to biopic simulacra, and I’ve thought about lodging a formal protest with the makers of the planned four-part Beatles epic. The following are my picks for the few times musical biopics did the music and the lives some justice.

The Beatles’ Hamburg period was a key part of their rise, thoughtfully realized here. Plus, the guy playing Paul McCartney was a striking lookalike:

Maybe not a great movie, but the tragic fall of the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones certainly deserved its own feature:

The late Chadwick Boseman shone in this gem about the complex Godfather of Soul, James Brown. Needless to say, a great soundtrack:

Though not technically a biopic, this semi-fictionalized dramatization of the real meeting between the President and the King was well-acted by Michael Shannon and Kevin Spacey, and darkly funny:

Brian Wilson’s poignant descent into mental illness and dependency is explored via the dual casting of Paul Dano and John Cusack – Dano looks more the part, but both actors find the Beach Boy’s vulnerability: