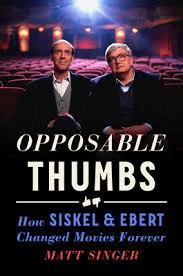

The short rejoinder to the title of Matt Singer’s 2023 book Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever is: Not in a good way. Singer charts a breezy and upbeat portrait of the two Chicago newspaper critics who became celebrity TV movie reviewers with a patented on- and (to a lesser extent) off-air rivalry, but he doesn’t much acknowledge their long-term influence on cinema and public discourse. In their heyday of the 1980s and early 1990s, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert were as visible as many of the actors and filmmakers whose works they assessed, but over time the visibility served only to degrade the significance of acting, filmmaking, and movies themselves.

Originally produced out of their home city and aired on the Public Broadcasting Service, Siskel and Ebert’s Sneak Previews was a novel experiment in showing two reporters from competing news outlets discussing the latest theatrical releases, their points illustrated with carefully extracted snippets from the films in consideration. The combination of honest – sometimes scathing – judgements and sample scenes was unusual in the television of the era, and the show won an appreciative audience of dedicated movie buffs. But eventually the studios began providing all TV networks with prepackaged “electronic press kits,” and a crop of telegenic film enthusiasts began to dispense their own brief summaries-slash-reactions on many stations, as the line between criticism and promotion started to blur. Siskel and Ebert were never beholden to Hollywood in the sense of being obligated to tout products they privately didn’t like, but their platform of showcasing new pictures with incidental commentary was widely copied by lesser talents for less discriminating tastes.

Sneak Previews and its syndicated follow-up, Siskel & Ebert At the Movies, also coincided with the rise of home video and the ebbing wave of adventurous and complex American cinema, which stretched from Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Easy Rider (1969) to Apocalypse Now (1979) and Raging Bull (1980). In between were The Godfather, Five Easy Pieces, A Clockwork Orange, American Graffiti, Nashville, Annie Hall, Taxi Driver, and many other classics. But by the time Siskel and Ebert were winning big ratings, the industry had become increasingly dominated by the likes of Star Wars, ET, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Friday the 13th, and Porky’s: easily digestible blockbusters whose visceral appeal bypassed anything like the thoughtful engagement a professional or amateur cineaste might provide. Opposable Thumbs scarcely mentions the intellectual arguments of film critics Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, and makes no reference at all to the artistic insights provided by James Agee, Stanley Kauffmann, John Simon, or the Cahiers du Cinéma, no doubt because such writers and journals belonged in the world of print, whereas Singer’s book is about a time when movies and television were essentially morphing into the same medium.

That wasn’t directly the fault of Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, who could each champion low-budget indie productions and who weren’t concerned about upsetting powerful stars or producers with bad reviews; I fondly recall the first seasons of Sneak Previews on PBS, where My Dinner With Andre or 1973’s Badlands were given as much or more attention as overhyped vehicles for Burt Reynolds or Bo Derek. But the duo parlayed their routine into a predictable format that precluded subtle exchanges of ideas – neither man comes across in Singer’s account as particularly likeable, and their mutual antagonism seemed to stem more from petty personal differences than deeply held beliefs about film theory. Their shows also expanded the burgeoning field of televised argument, whereby every topic was turned into fodder for entertaining conservative-liberal, pro-con, thumbs up-thumbs down yelling matches rather than constructive discussions. “Millions of Americans, including many who had very little interest in movies, tuned in to Siskel & Ebert every week to see what they would fight about next,” Singer writes. He means to celebrate his subjects’ success, but he unintentionally highlights their failing. Just when movies were beginning a long slide into mere “content” that continues to this day, the career of Siskel and Ebert, in spite of themselves, contributed to the descent.