The crisis of addiction that has plagued cities across North America, particularly smaller centres already affected by economic decline, is something I have witnessed firsthand. I grew up in a northern Ontario steel town that was buffeted by layoffs from the 1980s onward, and was being further hit by waves of downsizing and depopulation when I relocated there with a young family for a few years in the 2010s. But by that time the new element of opioids like fentanyl and MS Contin had entered the picture, as jobless youth and adults now faced the additional distraction of habit-forming and potentially lethal drugs. Visiting my birthplace recently, their impact on the streets and neighborhoods I knew in better times was all too plain.

Of course, it’s long been true that every place has its criminal – and chemical – underworld. In my mercifully out of print 2008 memoir Arcadia Borealis: Childhood and Youth in Northern Ontario, I described the subculture of teenage dope smoking my buddies and I immersed ourselves in circa 1986, hanging out in sunny crash pads and darkened back alleys with recreational substances. The drugs of that era, though, at least the ones we took, were the cannabis derivatives of hashish and hash oil; the more adventurous of us sometimes tried LSD for an extra mind-altering experience. All of it had been diluted or cut to facilitate being smuggled in marketable quantity from metropolises like Toronto to remote locations along the northern highway – hash oil, I wrote in Arcadia Borealis, was “to good weed what backwoods moonshine is to fine champagne.” And our guiding spirits in partying were hippie icons like the Beatles, Pink Floyd, or Abbie Hoffman, as we tried to recreate our own Woodstocks or Abbey Roads twenty years late. It may have been stupid and self-destructive, and in those days illegal, but it was generally fun. And nobody died.

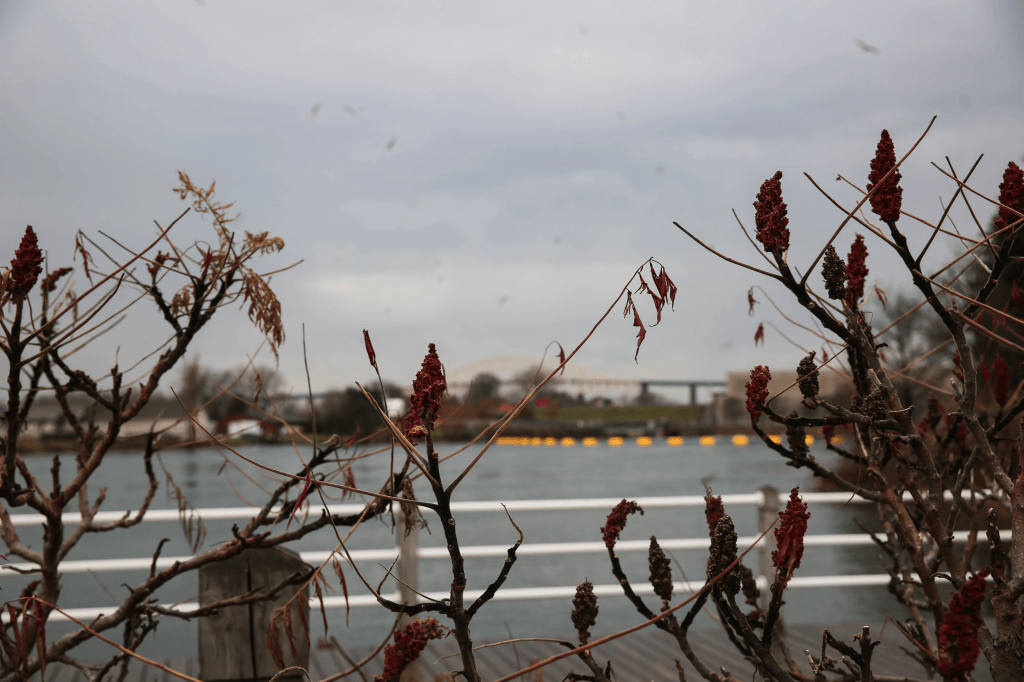

Today, in contrast, there’s something surreal about driving into isolated communities where a thriving industry of licensed marijuana retailers advertise their services on roadside billboards, before passing through a downtown core of boarded-up shops, seedy consignment outlets, government- or volunteer-run “support” facilities, and a wandering underclass of aimless, strung-out fentanyl addicts. Quaint old houses where full-time steelworkers and their families once lived, and the hospital where I was born, are now drug squats. It’s like a zombie movie with a Bruce Springsteen soundtrack. Per capita, my home town has one of the highest rates of opioid-related deaths in Canada, and it’s also recorded an increase in petty theft and violent crime, as users and dealers fight over debts and customers, and steal from small businesses and unlocked cars to pay for their next hit. You don’t get a sense of any countercultural affectations here: no one has time to fight the System or form a band when they’re focused only on finding another source of supply. Every city in North America – including my current residence of the national capital – is undergoing a similar plague of toxic opiates, but the plague’s toll is proportionately higher, and more conspicuous, in the cities of the Rust Belt.

Who’s to blame? It could be any number of culprits. Globalization has gutted the manufacturing and resource industries that were once the main employers of small communities across the continent. Technology has aggravated the gap between the skilled and unskilled classes, while the modern deluge of electronic media constantly reminds those on the wrong side of the divide that they’re missing out. Well-meaning social programs have tended to enable or excuse addiction as much as they discourage it, providing the vulnerable with ready-made victim identities that give meaning to otherwise chaotic lives. The notoriously corrupt municipal politics of mill towns and border cities has allowed for an underground trade in illicit product while prosperous local officials skim proceeds off the top and look the other way. Tourism-minded civic boosters don’t want to know about the problem at all. And maybe even the legacy of the sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll ethos my friends and I once celebrated has been indirectly passed down to later generations, shedding the music and the attitude and leaving only the drugs themselves.

I throw no shade on the healthy, productive citizens who still reside in these places. It’s easy to ask why they don’t pack up for better opportunities elsewhere and leave their dying towns to the fentanyl zombies, but there are still people who have built decent careers and deep personal ties in burgs that outsiders might see characterized only by poverty and despair. The best they can do is to continue to set an example of the paths that remain possible – just – where idleness, despondency, and intoxication are the more obvious options. For myself, I’m glad to have escaped, but sad that I had to, and while anyone’s old haunts go through a lot of changes over fifty years, it hurts to see how haunted mine are now.