One of the most recurring themes in pop musicology – a myth which critics have long debunked yet which they seem forever bound to debunk again – is the dubious talent of the Beatles’ drummer Ringo Starr. From the quartet’s rise to fame and their spectacular career in the 1960s, and throughout their posthumous life as rock legends, Ringo has often been regarded as the weakest link in the Beatles’ chain: a shallow intellect, an irredeemably unhip celebrity, and a barely competent backup player. Today you can find hundreds of printed and online rebuttals of these smears, but why the smears persist may tell us more not just about Ringo Starr himself but the very nature of rock ‘n’ roll and pop culture generally. To be clear, I endorse the late Ian MacDonald’s appraisal in Revolution In the Head: “[L]ong travestied as an amiable mediocrity riding The Beatles’ coattails, he is nothing less than the father of modern pop/rock drumming – the modest man who invented it.” Yet how did the travesties ever gain traction to begin with?

Ringo Starr, of course, was the last member to join the Beatles, just after they won their first recording contract, and after John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison had already known each other and been playing together for several years. He sang a few songs from the group’s catalogue (the most familiar are “Yellow Submarine” and “With a Little Help From My Friends”) and received a songwriting credit on a handful (notably “Octopus’s Garden”), but he was hardly their most prolific composer or strongest vocalist. He did not contribute at all to the Beatles’ softest material, which includes the perennials “Yesterday,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Blackbird,” and Abbey Road’s rhapsodic “Because.” At a few points in their trajectory he was not the band’s drummer: one version of 1962’s “Love Me Do” was played by studio pro Andy White; journeyman Jimmy Nicol sat in on some gigs during the Beatles’ international tour of 1964 when Starr was hospitalized with tonsillitis; and McCartney took over behind the kit during the fractious 1968 sessions for the White Album (The Beatles), on “Back in the USSR,” “Dear Prudence,” and “Martha My Dear,” and subsequently on 1969’s “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” when Starr was unavailable at Lennon’s short notice. And the Beatles movies A Hard Day’s Night and Help! fixed Ringo’s character as the group’s lovable doofus, part mascot, part ballast.

As the foursome broke apart, and in their first years as solo artists, Ringo Starr’s public persona contrasted with that of the other ex-Beatles. He was not a complex, sometimes tortured social activist like John Lennon, an all-round musical chameleon like Paul McCartney, nor a questing spiritual troubadour like George Harrison, but mostly a mid-level TV and movie entertainer. As higher-browed analysts began to dissect the Beatles’ lives and work, they initially heard Lennon’s confessional lyrics, McCartney’s effortless gift for melody, and Harrison’s solemn depths; Ringo was just the guy who kept time, usually at the others’ direction. In their final phase as a band, assessed Greil Marcus in 1979, “John was cultivating his rebellion and his anger, Paul was making his Decision for Pop; George was making his Decision for Krishna; and Ringo was having his house painted.” A Rolling Stone music guide from 1992 summed up their separate roles: “John Lennon (rebel genius), Paul McCartney (perfectionist craftsman), George Harrison (mystic), and Ringo Starr (clown).”

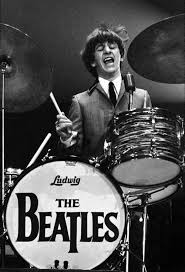

In the wake of the Beatles’ huge success, countless rock bands of a similar configuration emerged, many with drummers as audible and visible as Ringo – or more so. The Rolling Stones’ Charlie Watts, the laconic, jazz-trained hipster whose cool grooves propelled the quintet’s snarling R&B; the Who’s Keith Moon, the hyperkinetic loose cannon who sounded like a barrage of them; Mitch Mitchell and Ginger Baker, virtuosi whose chops matched the guitar heroism of their bandmates Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton; John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, Bill Ward of Black Sabbath, and Ian Paice of Deep Purple, hard-living heavy hitters who laid the foundations of heavy metal. By the 1970s, rock drumming encompassed everything from the fusion-like prowess of Rush’s Neil Peart, an expert technician who was also the trio’s lyricist, to the labyrinthine reggae meters of the Police’s Stewart Copeland. Next to all these players, and more besides, to the average ear Ringo Starr’s skills seemed at best rudimentary. Some drummers wrecked hotel rooms and took twenty-minute solos on multi-tom, double-bass fortresses, and then there was Ringo, cheerfully thumping away on his simple Ludwig set, almost drowned out by a house full of screaming teenage girls.

The most egregious charges against Starr were eventually disproven, but their effects lingered. For a long time the great American drummer Bernard Purdie claimed it was actually him on the Beatles’ records (in fact he overdubbed Starr’s predecessor Pete Best on some early 1960s Hamburg tracks, released to cash in once the Fab Four became global superstars). Given that Paul McCartney was known to have played drums in the studio, and definitely drummed on some of his own Wings albums, it was a short leap to suspect that all the Beatles’ drum parts were performed by someone besides Ringo. Then there was the apocryphal quip misattributed to John Lennon, that Starr was “not even the best drummer in the Beatles” (the line was a British comedian’s), which further reminded listeners, fairly or not, that Starr was the Beatles’ most dispensable member.

Again, most of the putdowns have by now been discredited and Ringo’s artistic reputation is today secure. The Beatles themselves have a stature approaching secular sainthood; no one dares blaspheme an individual Beatle. In 1980 Lennon went on record to call his former accompanist “a damn good drummer. He was always a good drummer.” Other famous stickmen, including Watts, Moon, Copeland, Max Weinberg of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, and Jim Keltner, have delineated exactly how Starr established the parameters of their genre, and many lesser-known drummers also speak reverently of his unshakeable rhythms, inimitable fills, and unimprovable contributions to Beatles classics like “I Feel Fine,” “Rain,” or “Come Together.” Reinforced in latter-day documentaries like Get Back and Beatles ’64, the conclusion seems to be that nothing in the Beatles’ canon – no song, no concert, no demo track or alternate take, no isolated performance – could have come from anything but sheer musical brilliance, including Ringo Starr’s. “There were no passengers in this group,” Ian MacDonald wrote of their landmark 1963 hit “She Loves You,” “and, when a situation warranted it, their drive to achieve was unanimous.”

Yet considering the place of percussion in western music, and certainly in the popular forms of jazz, country, and rock ‘n’ roll, it’s difficult not to relegate percussionists to a secondary rank behind singers and songwriters, as well as horn players, pianists, or guitarists. Think of the old joke – Q: What do you call someone who hangs out with musicians? A: A drummer. Even as the sound of drums became more pronounced within particular categories (especially when played by swing stars like Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich, or bebop greats Max Roach and Philly Joe Jones), it was the harmonies and the melodies – the tunes – that audiences heard first. Drummers could only do so much. Although Ringo Starr’s drumming could complement Beatles songs sublimely, the songs were supreme. On “Twist and Shout,” “If I Fell,” “Day Tripper,” and “Get Back,” for example, he exemplified the less-is-more aesthetic of solid support, showcasing the others’ input to maximum effect, but on “Words of Love,” “All You Need Is Love,” and “Hey Bulldog” it could almost be anybody playing. While a Mitch Mitchell or a Max Weinberg might not have done anything better with the cuts, they might have done something more distinctive.

The Beatles’ immense triumph also established the ideal of popular rock groups as uniquely compatible ensembles whose music no other combination of personnel could replicate, an often misleading image cherished by fans but dismissed by record producers and group members themselves. Three-, four-, and five-piece outfits were frequently promoted as democracies in microcosm, when in truth there were always one or two undisputed leaders, and Ringo wasn’t one of them. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr were obviously close colleagues and sensitive musicians who played well off each other, but they came to resent the hype that portrayed them as forever fated by destiny to their positions within the band. Permanently enshrined in the pantheon of pop music as the Beatles repertoire has become, many of the songs arrived by accident or offhand effort, rather than divine muse; even the “Lennon-McCartney” label on their titles obscured the reality that Lennon had nothing to do with writing “Hey Jude” nor McCartney with “Revolution.” Similarly, some devotees have ascribed a cosmic inspiration to the Beatles’ most expedient 4/4 backbeats, a level of overpraise all the Beatles, including Starr, would probably disavow. Asked yet again about a prospective Beatles reunion, no less an authority than Lennon was adamant: “Whether George and Ringo joined in again is irrelevant. Because Paul and I created the music, okay?”

In fact many drum legends, among them Neil Peart and John Bonham, were last-minute recruits to their respective acts, just as the ever-fragmenting Black Sabbath carried on in several incarnations without Bill Ward and the Who substituted Kenney Jones for Keith Moon after Moon’s 1978 death, and later replaced Jones with, of all people, Zak Starkey, son of Ringo Starr. Any professional player, certainly, will have an idiosyncratic touch that sets them apart – but then, any professional player will have the ability to copy another’s touch accurately enough to satisfy average listeners. In recent years Ringo has even been introduced to drum on Beatles songs onstage with Paul McCartney, but the otherwise ecstatic spectators notice that McCartney’s regular touring drummer, Abe Laboriel Jr., plays along at the same time. The point is not that Starr wasn’t good at what he did, but that what was required of him was not fundamentally beyond anyone else’s musical range. This may account for the extremes of opinion directed at him over the decades: either he was an ordinary performer who lucked into the opportunity of a lifetime, or he was an exceptional talent and a perfect foil, without whom the whole thing couldn’t have worked. Really – and perhaps like a lot of legends from a lot of fields – Ringo Starr was a bit of both.