While historians have for decades researched and documented the US victory over Japan in World War II, recent studies have revealed just how devastating the war was for Japanese civilians, particularly those subjected to bombing raids by B-29 Superfortresses of the US Air Force. Barrett Tillman’s 2010 title Whirlwind: The Air War Against Japan, 1942-1945 and James M. Scott’s 2022 work Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Firebombing of Tokyo, and the Road to the Atomic Bomb describe the aerial campaigns that had laid waste to the cities of the Rising Sun even before Hiroshima and Nagasaki; it’s a disturbing chapter in a story that was already replete with them. Awe-inspiring as the operations were as displays of military air power, their awful human consequences should remain foremost in our memory.

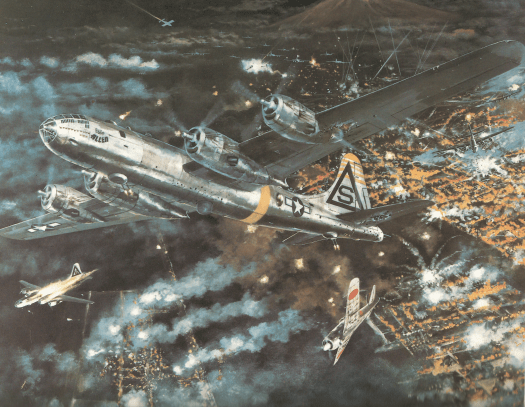

The Boeing B-29 was initially conceived as a long-range bomber that could strike European targets from North America in the event that Nazi Germany overran the entire continent, but it was only ever deployed in the war’s Pacific Theatre, where the oceanic distances from bases to targets were even more vast. Its designation as “Superfortress” denoted its evolution from the company’s earlier B-17 Flying Fortress model, and the two aircraft shared a roughly similar tailfin shape and four-engined configuration – but the B-29 was built to fly farther, higher, faster, and deliver more bombs than its predecessor, while armed by more guns, bristling from automated turrets, and the plane featured pressurized aircrew stations that eliminated the need for the oxygen masks and bulky protective clothing worn by fliers of the B-17 and every other warplane of the era. By some measures it was the most advanced machine to see service in the Second World War. The entire Superfortress program, in fact, cost the American treasury more than the other colossal enterprise with which it became inextricably linked: the Manhattan Project that produced the atomic bomb.

B-29s first attacked Japan from airfields in China and India in mid-1944 and then, as US forces slogged their way through bloody conquests of Japanese-held territory in the Pacific, from the islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. Raiders found they faced some of the same problems in Asia as American and British strategists had in Europe: treacherous weather that delayed, misdirected, or cancelled missions, navigational challenges that made for inaccurate bombing, intelligence gaps that made it difficult to determine the most crucial bombing objectives, and regular equipment failures (the complex new B-29s were especially prone to engine fires). One difference, however, was that the Japanese could not muster the kind of formidable air defences fielded by the German Luftwaffe from 1941 to the first months of 1945, including radar, anti-aircraft guns, and fighter interceptors. The staggering American Eighth Air Force casualties over Schweinfurt in 1943 and Royal Air Force losses over Nuremburg in 1944 were not replicated over Tokyo and Nagoya. “Overall, Japanese fighters were spectacularly ineffective against B-29s,” appraises Barrett Tillman.

American missions were still dangerous, though. The Japanese Army and Navy air forces had lost many of their best pilots earlier in the war, the country’s industrial resources had drastically declined as they retreated from their holdings in southeast Asia, and Japan’s isolated geography gave little scope for advance detection of incoming US bombers – but at least a few of the remaining planes they could put up against the B-29s, such as the Kawasaki Hayate, the Mitsubishi Raiden, and the twin-engined Kawasaki Toryu, were high-performance weapons capable of taking the big Boeings down. While the numbers of Superfortresses destroyed by Japanese fighters never became critical (more crashed due to mechanical issues than enemy action), B-29 crews could still expect to encounter some serious opposition in the air, at least until about the spring of 1945. The unfortunates among them who parachuted over the home islands were sometimes imprisoned, sometimes beaten or bayoneted to death on the spot.

In the final months of the war the US squadrons changed tactics, abandoning the traditional high-altitude precision targeting of factories or other installations for a technique that had already wiped out the German cities of Hamburg and Dresden: area bombing. Unimpressed with results to that point, and knowing the largely wooden construction of Japanese cities, General Curtis LeMay directed his command to fly in at lower heights, stripped of their defensive guns, and carrying payloads of incendiary bombs rather than high explosives. For the first time, LeMay made no pretense that his planes were out to surgically eliminate single facilities like train yards, manufacturing plants, or docklands. Instead, the Tokyo mission of March 9-10, 1945 burned some 10 000 acres of the city to the ground, about 63 percent of its commercial district, and killed an estimated 105 000 people. Anti-aircraft and fighter resistance was negligible. Only a few thousand feet above the inferno, from inside their B-29s, crews could smell human flesh burning.

Scott’s Black Snow vividly describes the nightmare that ordinary Japanese men, women, and children lived and died through:

The glow of the conflagration turned night into day, illuminating the capital as if it were noontime. Asphalt roads softened into a sticky goo that clung, like quicksand, to bicycle tires and shoe soles. The fires produced a deafening roar like a freight train, drowning out the cries of husbands separated from wives, children from parents…The winds sent bags tumbling down streets and ripped children from the grip of parents…Residents fled down narrow roads, which resembled tunnels through the flames. The superheated air caused people’s clothes and even hair to spontaneously ignite…The flames spared nothing…

Ever since the Tokyo raid, and the similar incendiary attacks on other cities that followed, a moral asterisk has been attached to America’s defeat of Japan. The atomic bombings of August 6 and 9 might be justified as the only way to shock otherwise suicidal Japanese leaders into surrender, but Curtis LeMay’s coldly calculated tactics of conventional warfare, against an already much weakened enemy, actually wrought more deaths than were incurred at either Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The general’s Cold War career as the hawkish head of the US Strategic Air Command, and later as running mate to the segregationist presidential candidate George Wallace in 1968, further fixed the stereotype of the fanatical right-wing military chief obsessed with destruction for its own sake: LeMay and his subordinate General Thomas Power (who flew on the Tokyo mission and succeeded his boss to run SAC in the 1960s), were models for the psychotic General Jack D. Ripper and the war-loving General Buck Turgidson in Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 satire Dr. Strangelove. And Robert McNamara, Lyndon Johnson’s Defence Secretary during the Vietnam debacle, had advised on the “efficiency” of the firebombing techniques when serving as a junior officer under LeMay in World War II, a legacy he reflected on in the haunting 2003 documentary The Fog of War. B-29 Superfortresses remained in the US arsenal during the Korean War, where their bombs were once again aimed at teeming Asian population centres and killed several hundred thousand people, directly or through starvation.

Over eighty years afterward, the Tokyo raid remains the most lethal single military operation – and certainly the deadliest urban fire – in history. The sleek silver Boeing B-29 Superfortress, though in many ways a magnificent feat of aeronautical engineering, will always be associated with the near-Biblical rain of ruin it poured on Japan in the final months of the Second World War, and the plane’s leading exponent Curtis LeMay may have unintentionally articulated the chilling relativism that undermines every political and ethical principle still invoked in conflicts around the world today. In a widely quoted comment, when later asked about the morality of the apocalypse he created in March 1945, he replied: “I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal. Fortunately, we were on the winning side.”