Very shortly after the attacks of September 11, 2001, the reaction of hundreds of millions of onlookers divided into two broad camps, which have scarcely agreed on any other issue in the more than twenty years since. One type of response came from established politicians, popular historians, veterans’ organizations, and a surprising number of erstwhile liberals and leftists:

- “But straight away, we meet people who complain at once that this enemy is us, really…I have no hesitation in describing this mentality, carefully and without heat, as soft on crime and soft on fascism.” Christopher Hitchens, “The Fascist Sympathies of the Soft Left,” The Spectator, September 29, 2001

- “But all too often, the pacifists leap to another argument – that the tragedy of September 11th was the inevitable result of America’s arrogant imperialist foreign policy. As the cliché of the moment has it, America is now reaping what it has sown. This is wooly thinking at best…Islamist fundamentalists don’t object to the things that campus leftists dislike about America. They object to the things that they like, such as freedom of speech, sexual equality and racial diversity.” “Treason of the Intellectuals?,” The Economist, October 6, 2001

- “No government anywhere has the right to neglect the safety of its own citizens – not least against an enemy that swears it will strike again…In this purist insistence on reducing America and Americans to a wicked stereotype, we encounter a soft anti-Americanism that, whatever takes place in the world, wheels automatically to blame America first.” Todd Gitlin, Mother Jones, January/February 2002

- “The radical failure of the left’s response to the events of last fall raises a disturbing question: can there be a decent left in a superpower?…Maybe the guilt produced by living in such a country and enjoying its privileges makes it impossible to sustain a decent (intelligent, responsible, morally nuanced) politics.” Michael Walzer, “Can There Be a Decent Left?,” Dissent, Spring 2002

- “There is nothing new about objections from the American left to the exertion of US power abroad…Yet this time the far left’s reaction was strikingly reactionary. If the left seemed as anti-American as it was anti-terrorist, that was because it was in fact anti-everything, offering no program for American self-defense in the face of a direct attack and no substitute for either Western materialism or Islamic fundamentalism.” Jonathan Rauch, “The Mullahs and the Postmodernists,” The Atlantic, January 2002

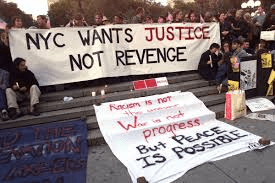

The second general trend of thought in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 was expressed by academics, labor groups, political progressives, and students, illustrated in the following public statements:

- “Let’s by all means grieve together. But let’s not be stupid together…[The attacks were] undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions.” Susan Sontag, “The Talk of the Town,” The New Yorker, September 24, 2001

- “Our broken promises, perhaps even our destruction of the Ottoman Empire, led inevitably to this tragedy.” Robert Fisk, “Terror In America,” The Nation, October 1, 2001

- “The history of the last fifty years is the history of US war and repression in one Third World country after another…The media keep banging the drums, and by the time you read this, it’s likely the United States will be raining violence across the globe.” Matthew Rothschild, “A Terror-Filled Day,” The Progressive, October 2001

- “[T]he US has been able to impose, subvert, poison and kill peoples [sic] with impunity…the US state is the greatest organizer and perpetrator of terror in our times.” Canadian Dimension, November-December 2001

- “[T]he path of US foreign policy is soaked in blood…the West for five hundred years has believed it can slaughter people into submission…[T]he United States is the most dangerous and the most powerful global force unleashing horrific levels of violence all over the world.” University of British Columbia Professor Sunera Thobani, Women’s Resistance Conference, October 1, 2001

- “[The American] flag stands for jingoism and vengeance and war…There are no symbolic representations right now for the things the world really needs – equality and justice and humanity and solidarity and intelligence.” Katha Pollitt, “Put Out No Flags,” The Nation, October 8, 2001

This same point-counterpoint, with-us-or-against-us pattern has recurred in the wake of the Hamas attack against Israel on October 7, 2023, and the Israeli military’s subsequent mobilization against Hamas-controlled Gaza. Traditional news publications, campus communities, and actual citizens and legislators are taking sharply delineated sides: Israel is a colonial oppressor; Hamas is a genocidal terror party; support for Palestine is anti-Semitic; support for Israel is Zionist imperialism; there’s no simple answer; yes, there is. The more firmly held the outlook, the greater the indignation at those who don’t share it. Today’s conflict, like that of 2001 and after, is not just between opposing geopolitical powers on a Middle Eastern battlefield, but between opposing cultures within our own society. Just as we saw over two decades ago, real violence and death have become fodder for an abstract war of ideas and rhetoric – there’s the fighting far away, with horror and bloodshed, and there’s the fighting on Facebook and X, with upset emotions and unfollowed friends. Neither clash is likely to end with a clear-cut victory.

In some ways the competing words and images are just a function of contemporary media dynamics, wherein even trivial developments like celebrity scandals trigger heated exchanges that anyone with a phone can follow and join in on. Hard news like massacres or wars invite even wider and angrier commentaries. Yet it’s uncertain whether all this constitutes a genuine public conversation that might eventually lead to a unifying conclusion, or whether it’s simply a lot of individual voices taking the opportunity to weigh in on something most of them are only tangentially connected to. Avowing your solidarity with Israelis or Palestinians is easy on Reddit or Instagram, in the same way it was easy to select Fox News or al-Jazeera for your evening news in the autumn of 2001. The choice advertises your personal beliefs, sure, but it’s nullified by someone who’s picked something else.

Such a glut of electronic options as offered by the 500-channel universe prefigured the by now notorious sequestering of thought promoted by countless digital platforms and customized feeds, through which separate audiences are fed separate interpretations of the same underlying story, and it takes a special effort to find anyone saying anything besides whatever a proprietary algorithm has determined you already want to hear. Much of the outrage that followed September 11 wasn’t directed directly at Osama bin Laden, or for that matter at George W. Bush, but at some pundit or talking head who’d made the wrong observation on the wrong panel show. It wasn’t about saving lives or changing the world anymore. It was about winning an argument. Twenty-two years hence, the same imperative has simply gone viral.

Of course debate and dissent are fundamental to democracy. It would be surprising if awful events like 9/11 and the Hamas strike didn’t spur a range of differing views on what they signify and what authorities should do about them. But democracy is also about popular opinion and majority rule, in which debates gradually wind down and dissent doesn’t always expand into consensus. Plenty of other contentious issues – to do with race, gender, health, crime, economics – go through parallel schisms, as they generate eloquent op-eds, impassioned protests, and storms of tweets and retweets, before history moves on and only time tells whose views have prevailed. The righteous anger felt toward al Qaeda and the Taliban in 2001 was expended in the catastrophic Iraq war and the long Western investment of blood and treasure in Afghanistan, which concluded in an ignominious retreat and the Taliban’s return to power. The anger was real; waterboarding, extraordinary renditions, Abu Ghraib prison, and thousands of dead soldiers and civilians were real too. So who was more prescient right after the towers fell? The Economist or The Nation? The late Christopher Hitchens or the late Susan Sontag? Who gets to render a final verdict in hindsight, and who wants to rethink their original positions?

As assured as you may be in your stance, and as forcefully as you try to persuade others of its wisdom, what everyone else believes – and how they act on it, and what transpires from their actions – is not up to you. It’s not necessarily that the people you disagree with are right. It’s that they can’t be written off. One thing progressives have had to learn the hard way in recent years is that they dismiss Brexiteers and MAGA Republicans at their peril: resentful populists may not be able to muster coherent philosophies, but there are enough of them to win elections and referendums. Likewise, in 2025, anti-war marchers don’t seem to have a lot of viable solutions or sound logic on their side, but they also comprise a large constituency that raises funds, posts on social networks, demonstrates in well-attended rallies, and votes. Perhaps they’re only caught up in shallow relativism and old bigotries; on the other hand, perhaps they represent a fateful swing of the political pendulum. There are cases that today feel convincing when summed up in podcasts or editorial columns. But they may not convince anyone protesting on the streets of Toronto or London, any more than they ever convinced in the rubble of Kandahar, Baghdad, or lower Manhattan.