Those of us who write professionally about popular culture have to balance the detached appraisal of the critic with the partisan appreciation of the consumer. After all, the movies, music, television and other media we review aren’t just artistic statements but leisure products as well, so they ought to be described with some of the same subjective enthusiasm any follower or collector might feel about their favorite car, food, or clothes – there’s really no accounting for taste, so why not celebrate how unaccountable our tastes can be?

Pioneers in this approach include Pauline Kael (1919-2001) and Lester Bangs (1948-1982), who covered Hollywood films and rock music, respectively, with a first-person idiosyncrasy meant to capture the private pleasures to be found in what was often crassly commercial, even disposable, material. Rather than striving for the dry impartiality of older columnists, Kael, Bangs, and their many imitators tried to fuse commentary with confessional, employing a lively, quasi-conversational voice that sounded like you were listening to the initial impressions of someone who’d just seen the movie or heard the album. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t. Sometimes their essays brought a fresh and exuberant honesty to the craft, but sometimes they drifted into a stream-of-consciousness verbosity that obscured how little they actually had to say.

This tradition lives on in the books of Rob Sheffield (Dreaming the Beatles, Talking to Girls About Duran Duran, Love Is a Mix Tape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time), Steven Hyden (Your Favorite Band Is Killing Me, Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic Rock), and leading light Chuck Klosterman (Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs, Eating the Dinosaur, Fargo Rock City: A Heavy Metal Odyssey in Rural North Dakota). Taking on a megamall of work from various media – mostly music, but cinema, TV, the internet, and fashion as well – their recurring device is to intersperse pseudo-authoritative analysis of bands or shows with autobiographical accounts of the personal ephiphanies they experienced through listening or watching. They also try to map what they imagine to be entire universes of pop styles – e.g. how one act’s rock video was influenced by an earlier sci-fi film, which in turn had a curious afterlife in a cult comic book series adapted into an arcade game later referenced in an early season of The Simpsons, etc. – conveying a constant sense of being trapped in a dorm room with a first-year humanities major as he classifies every last item in his mental archive of entertainment trivia, before going on to parse the subtle differences between the four or five student cliques at his old high school.

To call Klosterman, Sheffield, Hyden et al “self-indulgent” is almost to miss the point. Or rather, the self-indulgence is the point: their curatorial judgement is supposedly so astute that following the trail of their thoughts as the judgements form is a rewarding journey. Their techniques make them the Gen X or Millennial versions of Pauline Kael or Lester Bangs, in the digressive, chatty structure of their prose (with lots of parenthetical asides, footnoted qualifiers, and incidental wisecracks), except the writers are more steeped in technology and mass culture and less aware of anything outside of them, including the tech and culture industries themselves. To this newer generation, pop trends are more like natural phenomena, to be understood the way an astronomer understands the night sky, rather than economic forces to be understood, at least in part, by exploring the decisions of producers and marketers. They publish stories about their immersion in communities of Beatlemaniacs, Swifties, or metalheads, not about how the communities arose to begin with.

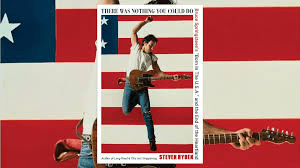

Take Steven Hyden’s 2024 title There Was Nothing You Could Do: Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The USA” and the End of the Heartland. The problem here is not the author’s knowledge of Bruce Springsteen’s music and career, which is considerable, and it’s certainly not with Springsteen himself, an important artist with a devoted following. Instead the problem is Hyden’s inability to separate his childhood fandom from his adult assessments, so there are lots of sentences like “In the mid-eighties, loving Bruce Springsteen was no longer something that could define you,” and “People like postfame records because they enjoy the idea of someone who is not them not understanding the record as well as they do” – firsthand, unfalsifiable generalizations presented as critical truths. There Was Nothing You Could Do likewise often describes how the musician “famously” said or did something, as if Springsteen’s celebrity merits as much scrutiny as his catalogue of songs and performances; as with similar documents, it’s difficult to tell where the hard research ends and the rambling think piece begins.

Of course, show business does inspire an infinite number of interior responses in its audiences, and the tensions between public mythologies and backstage realities are worth studying. But scribes like Hyden, Rob Sheffield, and Chuck Klosterman mostly focus on their own responses to the mythologies, and their books are better categorized under memoir than music. No question, your emotional relationship with familiar entertainment and entertainers can spur fascinating meditations on culture, talent, and identity. Just not for someone who is not you.