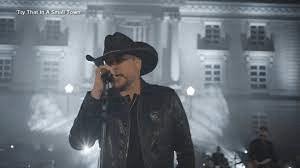

A recent episode of publicity and show business spilling over into the field of sober editorial commentary concerns not a blockbuster movie, a banned book, or a brand of beer, but a country music single. The controversy over Jason Aldean’s 2023 hit “Try That In a Small Town” – the song and its video were accused of promoting MAGA-style assaults against demonstrators and lawbreakers, and it was pulled from rotation on the Country Music Television network – epitomizes how deeply today’s entertainment has become politicized, just as much as politics has morphed into a form of entertainment. Yet “Try That In a Small Town” was only one of a long line of populist works that includes numerous golden oldies, certified classics, and even a few lingering outrages. Musically, Aldean’s piece was pretty routine, but its message puts it in a notable tradition.

Critics still haven’t figured this tradition out. For most, the sudden topicality of “Try That In a Small Town” was explained solely as a Trumpian call to violence in a polarized society. “Aldean’s combative new song…offers a musical riff on the same core message that Trump has articulated since his entry into politics,” wrote Ronald Brownstein in the Atlantic; “Its violent revenge theme is common in conservative rhetoric, whether it’s gun advocates talking about how they need AR-15s to fend off home invaders or wage war on the government or Trump telling cheering crowds about his desire to inflict violence on liberals,” said Paul Waldman in the Washington Post. The Toronto Globe and Mail‘s Marsha Lederman tortured her metaphors to expose the song’s true purpose: “It’s a call to action for vigilantism that carefully toes the dog-whistle line,” she told her readers, few of whom would probably have paid attention to the tune otherwise. As so often happens lately, a fundamentally trivial bit of pop culture was freighted by both friends and foes with more urgency than it deserved, becoming a proxy war in a conflict that’s become intractable on the more conventional fronts of elections and legislatures.

Indeed, there are older and more impactful symbols of populist resistance – and better ones. An obvious antecedent to “Try That In a Small Town” is Merle Haggard’s 1969 smash “Okie From Muskogee,” a catchy, twangy vent against marijuana, LSD, sandals, and San Francisco hippies released at the height of the counterculture; Haggard’s other successes like “Workin’ Man Blues” (1969) and “The Fighting Side of Me” (1970) were just as defiantly unhip in the era of protest and psychedelia. They won him the admiration of Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, and millions of ordinary American listeners. A roadhouse jukebox of famous country numbers, including Tammy Wynette’s “Stand By Your Man” (1968), Barbara Mandrell’s “I Was Country When Country Wasn’t Cool” (1981), Hank Williams Jr.’s “A Country Boy Can Survive” (1982), Gretchen Wilson’s “Redneck Woman” (2004), among many others, have similarly articulated an unapologetic working-class whiteness that’s since become a cultural and political flash point. These were the original hillbilly elegies.

Rock ‘n’ roll, too, despite its rebellious rep, has at times sided with a blue-collar demographic – occasionally, it turned out that the Silent Majority wanted to make some noise. Just when flower power was peaking in the streets and on the record charts, Creedence Clearwater Revival scored massive hits of proletarian humility, with “Proud Mary,” “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” and the class-conscious “Fortunate Son.” Bob Seger’s “Mainstreet” and “Feel Like a Number” (both 1978), as well as John Mellencamp’s “Small Town” (1985), were celebrating rural uprightness and heartland integrity decades before Jason Aldean. Bruce Springsteen, of course, has championed Rust Belt resilience across his career, with the multiplatinum triumphs of The River and Born In the USA, and pointed themes of economic dislocation in “Badlands,” “My Hometown,” and “Youngstown.” And more inflammatory gestures came from the arena rock demagogue Ted Nugent, with the gun-toting libertarianism of “Stormtroopin‘” (1975), and from Guns n’ Roses’ “One In a Million” (1988), which invoked anti-immigrant, anti-Black, and anti-gay lyrics.

Other songs that have become staples of classic rock radio and Gen X playlists may have drawn their first fans from future Brexit backers, truck blockaders, or anti-vaxxers – think of the underemployed anger of Judas Priest’s “Breaking the Law” (1980), the martial glory of Iron Maiden’s “The Trooper” (1983), or the barroom lechery of AC/DC’s “Whole Lotta Rosie” (1977) and ZZ Top’s “Tush” (1975). Originally scorned by rock’s intelligentsia, the loyal followings won by such acts – and their undeniable economic clout within the industry itself – may have prefigured the surging waves of populist grievance that have for better or worse upset progressive agendas around the world. To contemporary journalists puzzling over the appeal of the raunchy Australian quintet, AC/DC’s late frontman Bon Scott described his constituency in terms that echo into our era: “The music press is totally out of touch with what the kids actually want to listen to. These kids might be working in a shitty factory all week, or they might be on the dole…There’s been an audience waiting for an honest rock ‘n’ roll band to come along and lay it on ’em.”

The most enduring expressions of red-state pride, or chauvinism, have been made by Lynyrd Skynyrd, the legendary Southern band whose 1970s concerts were performed in front of a Confederate flag. Today Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” and “Simple Man” are anthems for a significant bloc of socially tolerant but sternly independent voters, and the heavy metal honky-tonk of their “Saturday Night Special,” “Gimme Back My Bullets,” and “I’m a Country Boy” has hugely influenced the entire medium of country music (“Try That In a Small Town” sounded a lot more like Lynyrd Skynyrd than Merle Haggard). Members of Skynyrd’s core lineup later acknowledged their support for segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace. “To Ronnie, Wallace was not just a man who wouldn’t let blacks into college, he was a man who spoke for poor, uneducated people who didn’t have a voice,” said guitarist Ed King of the band’s vocalist and lyricist Ronnie Van Zant, who died in a 1977 plane crash. It says something about the evolution of right-wing character over the last fifty years that conservative values are now associated less with repressed military or religious leaders than with long-haired rock stars blasting a righteous mixture of bluegrass and rhythm ‘n’ blues.

What does this history of populist pop music suggest? The artistic merit of “Try That In a Small Town” may not be much, but it belongs with a broader category that’s memorably captured the legitimate outlook of a lot of real people, which we do well to acknowledge and which we dismiss to everyone’s detriment. Performers as diverse as Merle Haggard, Bruce Springsteen, Judas Priest and Lynyrd Skynyrd may seem to have little more than their celebrity in common, yet across several decades they and their peers have all reached sizeable segments of the public singing about the same recurring ideals of working-class identity: stoicism, anti-elitism, personal honor, allegiance to community and place, and an undercurrent of masculine bravado, all of which have become “problematic” outside of the radio station and the concert hall but which remain deeply felt by a vast public. Jason Aldean may have offered cultural theorists a convenient surrogate for Donald Trump in 2023, but then so too, perhaps, was Merle Haggard a surrogate for Ronald Reagan in 1969 and Judas Priest for alienated youth in 1980. In the long term, what were once considered fluke crossovers or marginal submarkets portended much bigger movements. Today’s theorists may want to listen a bit more closely.

For all their familiarity, then, the “dog whistle” charges frequently leveled against Jason Aldean’s “Try That In a Small Town” and comparable pieces – they’re really spreading hatred, just subtly – are easy to assert but difficult to prove. “There is not a single lyric in the song that references race or points to it,” Aldean defended at the time. Who gets to parse a political speech, or a commercial song, for hidden meanings, and is the worst interpretation necessarily the most accurate one? What’s to be afraid of? Is it tempting to read an objectionable subtext into material when its outward language might actually be persuasive? Dog whistles, usually picked up by would-be dogcatchers before any authentic dogs, have become progressives’ equivalent of the drug references or Satanic incantations that panicked parents used to detect in “Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds” or “Stairway to Heaven” – subjective perceptions that feed the reaction of enemies far more than they stimulate the response of fans.

Beyond this reflex to translate any earnest but contentious speech as merely coded prejudice (critics pointed out that the video for “Try That In a Small Town” was shot on the site of a 1927 lynching in Columbia, Tennessee), there is the persistent inclination to ignore the groundswell of support that such speech can gather, whether in airplay requests, Youtube views, digital downloads, or poll results. Several generations of liberal reviewers, pundits, and candidates in many countries have struggled to admit the existence of conservatives as anything but rubes, rednecks, or deplorables; the backlash, when it comes, can be disastrous. Just look where we are now.

At some point, even if we don’t like the music, or the politics, we have to concede that many others do, and that they too are our fellow citizens. Demonizing entire populations as latent bigots whose political and musical preferences deserve nothing but scorn has only fostered a resentful solidarity among hitherto accommodating people, pushed former moderates into living up to the labels imposed on them, and encouraged genuinely dangerous extremists. Likewise, condemning a mediocre country ditty as a far-right dog whistle may seem like a quick, patronizing point to score in the culture wars – and no doubt we’ll go through more such exchanges in the future, over similarly frivolous issues – but those who take that route may find that when they steer around Mainstreet, they exit out on the Highway to Hell.

Another fine article.

It is interesting, too, when songs are misinterpreted and adopted in this way like “Born in the USA.”

Yeah, Springsteen was not happy when Reagan appropriated his message – “Born In the USA” is a lot more complicated than “Morning in America.” Thanks for reading.

J

Interesting read. I’ll admit I’ve managed to avoid hearing this one yet, as much because IMO Aldean just makes bad music, even by modern mainstream country standards as because of the controversy. I’m all for controversial music if it’s warranted but the music has to be good. I honestly hadn’t thought of it in context with the music you reference here, and that’s to my fault. He’s definitely not doing something out of line with a long history of tradition.

Some thoughts/random asides on some of your references— I’ve always heard that “Okie” was written by Haggard from his father’s perspective and was more than a little tongue in cheek. “Breakin’ the Law” was likely protesting anti-gay sodomy laws as Halford was closeted (and it’s great to imagine all the teen metalheads singing along cluelessly oblivious to that). Skynard, at least chief songwriter and singer, weee actually hippies at that point, “Saturday Night Special” called for gun control and even “Sweet Home Alabama” was up for interpretation given Van Zandt’s Neil Young fandom and those “boo-boo-boos” at Wallace’s reference.

I think we’re moving into an era where there’s no room for nuance, ambiguity, or transgression on mainstream art either on behalf of the artist or listener.

By the way, have you seen the related controversy over “Rich Men North of Richmond”?

Thanks for reading and commenting. I go into a lot more detail about this topic, including the complex layers of meaning to the work and images of Skynyrd, Priest, and Haggard in my 2021 book “Takin’ Care of Business: A HIstory of Working People’s Rock ‘n’ Roll” (You’re right that “Okie” was written partly in jest). The politicization of everything – every song, show, or movie gets classed as either Ours or Theirs – is certainly rampant these days – from what I’ve heard, “Rich Men North of Richmond” is the latest to get categorized as such. I’d submitted this piece to an online mag who suggested I work a reference to “Richmond” into a revised version, but I don’t really know that song or artist well enough, so I posted the piece here. Such is blogging. Best – gc