Probably the two most influential horror stories of the last sixty years – and maybe the two most influential stories period – are Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist. Both began as popular novels that modernized the occult themes of witchcraft and demonology, formerly all but dicarded in a secular age; both were soon adapted into successful movies that reinvented the genre and spawned numerous sequels and remakes; both transcended their mediums to become folk-pop archetypes millions of people can still recognize even without knowing the primary sources. Finally, both Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist can be interpreted as commentaries on issues far outside their surface subjects. What were they trying to tell us?

Re-reading Ira Levin’s 1967 bestseller yet again, I have to concede that Rosemary’s Baby might be a superior work of fiction to its Satanic sister of 1971, William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. It’s shorter and more subtle, with a more ambiguous buildup that doesn’t telegraph its ultimate point. The Exorcist has greater shocks and reaches for a deeper spiritual message, but Blatty was a questing Catholic and Levin was a Jewish agnostic; Rosemary’s Baby is thus less credulous and more suspenseful. It’s significant, too, that while Blatty never wrote anything to match his biggest book, Levin authored two other hit novels which also played on contemporary cultural concerns, The Stepford Wives (1972) and The Boys From Brazil (1976), as well as the often-performed play Deathtrap (1978). No less influential a writer than Stephen King has acknowledged his admiration for Levin’s style, and Rosemary’s Baby features some of the same prose effects that subsequently became King trademarks, e.g.

The one-sentence paragraphs.

That draw out the tension.

Like this.

Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist each brought old superstitions into sophisticated urban settings peopled with showbiz types (Rosemary’s husband Guy is an ambitious actor, while The Exorcist‘s Chris MacNeil is a bona fide movie star), but it’s remarkable how many timely allusions Levin gets in. The controversial 1966 “Is God Dead?” issue of Time magazine is found in a doctor’s office; Guy once dated Piper Laurie, a real actress who went on to play in the 1976 movie of Stephen King’s Carrie; Guy and Rosemary attend a film screening whose invitees include Stanley Kubrick, before the director’s landmark 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, and his 1980 version of King’s The Shining; Levin’s villain Roman Castevet is the son of an infamous Satanist who’s cited as a peer of Aleister Crowley, a genuine occult figure whose image appeared on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band shortly after Rosemary’s Baby was published. These details help ground the fantastic plot in a plausible reality, as Levin later explained: “The topical references, the plays and books and news events that Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse talk about were all very deliberate.”

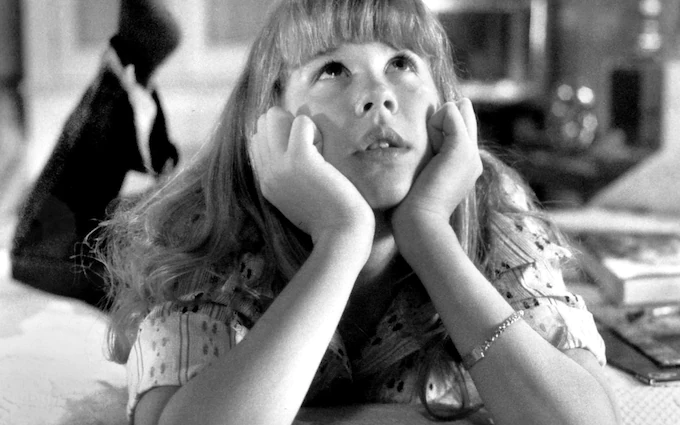

In 2025, of course, what might first strike new readers of Levin and Blatty is how two male writers focused their novels on sexually vulnerable females. Rosemary Woodhouse is a new wife who, after being drugged, is essentially raped and impregnated by the Devil; Regan MacNeil is a twelve-year-old girl possessed by a demon who voices obscenities through her, and forces the child to violate herself with a crucifix. The scenes are high points in the history of horror, but in the era of #Me Too and Donald Trump they may seem like business as usual. Though melodrama about damsels in distress long predated Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist, and countless slasher movies about victimized young women came after them, Levin and Blatty’s storylines depicted enlightened environments compromised by pre-Enlightenment belief: Rosemary is not a virgin and she’s broken with her family’s rigid Catholicism, and Regan’s mother Chris is a financially independent atheist single mom – yet they’re still confronted with the darkest mythologies of a patriarchal religion.

I can think of other comparisons between the two books. Their classic cinematic treatments were crafted by celebrated directors Roman Polanski (Rosemary’s Baby, 1968) and William Friedkin (The Exorcist, 1973); both have key reveals in the form of wordplay (Rosemary learns of Roman’s evil ancestry through anagrams, and Regan’s demonic gibberish turns out to be English in reverse); both seemed so authentic that subsequent generations took them to be accurate portrayals of real-life diabolism, particularly in the targeting of infants or children, which no doubt contributed the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s and the hysteria around day care centers supposedly infiltrated by secret cults of devil worshippers. Above all, each novel captured the underlying tensions of their time – rationalism versus faith, progress versus tradition, forward-thinking youth versus ancient doctrine, female autonomy versus male power – through narratives so compelling they still resonate today. If there is a realm where fictional characters have lives of their own outside the bounds of their original stories, I hope Rosemary Woodhouse and Regan MacNeil have met up there, to enjoy some tannis root tea and share the proud sorority of having together changed the world.