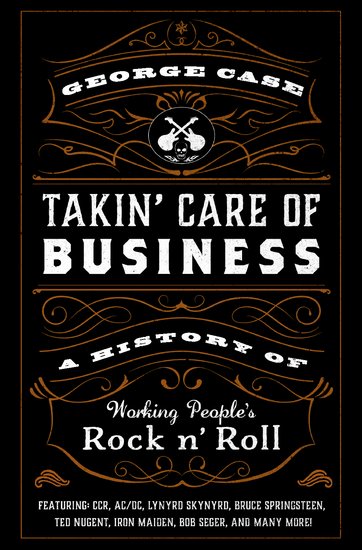

My most recent book, Takin’ Care of Business: A History of Working People’s Rock ‘n’ Roll, grew out of a post I originally wrote for this blog. I have long enjoyed (in addition to plenty of other music) the unpretentious, unrepentant sounds of AC/DC, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Aerosmith, Motörhead, and other guitar-based raunch from the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, and over the years I noticed that the core audience for these acts was increasingly tied to a demographic well removed from the usual hippie or punk progressives we’ve associated with the rock culture. Previous nonfiction works like Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash and J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy dealt with the same social class, but I wanted to impart a different spin on their analyses. How is it, I wondered, that fans who grew up with party-hearty heavy metal have come to embody the right-wing populism of the Tea Party and trucker protests? What changed in politics and society so that the 2016 Republican Party convention, where Donald Trump was nominated as presidential candidate, used the silhouette of a Fender Stratocaster guitar as its official logo? Could it be that Richard Nixon’s “Silent Majority” wanted to make some noise after all? My answers are explained in Takin’ Care of Business.

To chart the music’s shift from youthful rebellion to middle-aged resilience, I paralleled the success of key players – Creedence Clearwater Revival, Ted Nugent, country outlaws Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson, British bands Judas Priest and Iron Maiden, and heartland stars John Mellencamp and Bob Seger, to name a few – with political and especially economic changes affecting the business and the audience over generations. We’ve tended to think of rock as the soundtrack of postwar prosperity, but many of the artists I assess here built their constituencies from a working class buffeted by inflation, recessions, and globalization; Takin’ Care of Business reminds readers that there was always a section of the market that liked the sound of rock but had little patience for the utopian, let’s-change-the-world ideals of psychedelic acts or the acoustic introspections of singer-songwriters. And I found numerous backstage accounts and interview quotes to illustrate my thesis: “The music press is totally out of touch with what the kids actually want to listen to,” AC/DC vocalist Bon Scott told a journalist in the mid-1970s. “These kids might be working in a shitty factory all week, or they might be on the dole – come the weekend, they just want to go out and have a good time, get drunk and go wild. We give them the opportunity to do that.”

A second theme that emerged from my research was that the public response to many performers was frequently at odds with critical opinion, anticipating the resentment towards “elites” which is today such a volatile strain of worldwide politics. “To be told over decades that Steppenwolf, then Grand Funk Railroad, then Lynyrd Skynyrd, then Iron Maiden, then Styx, then George Thorogood, then Metallica, then Guns n’ Roses are strictly for rubes or racists is no more than a musical variation of the messages they’ve long received from arbiters of every other kind of prestige,” I wrote of this alienated cohort. The number of record buyers or concertgoers who chose crowd-pleasing hard rock over the alternative bands favored by the cognoscenti was reflected at the cash register, just as the analgous divides were later revealed at the ballot box. Gene Simmons of Kiss recognized the discrepancy early: “The rock press was always attracted to the Talking Heads, Television, the Ramones, the New York Dolls, the Sex Pistols – bands who couldn’t sell out a stadium or even an arena. There is a side to that media completely devoid of connection to the people who make up most of the rock audience.” My repeated point throughout was that what’s often dismissed as mere entertainment may hold a valuable insight into otherwise confounding issues. “Assessing the social history of the last few decades,” I asserted, “we learn a lot from studying important elections, pivotal legislation, traumatic wars, and transformative new technologies. But we can also learn a lot from picking through a stack of legendary vinyl records.”

I was very proud that, in a peak achievement of my literary career, Takin’ Care of Business was published by the prestigious academic house of Oxford University Press in 2021, giving me a platform with educators and students who can teach and learn from my combination of musicology and political theory. Invoking everyone from Margaret Thatcher and Barack Obama to Black Sabbath and Bruce Springsteen, the book offers a unique perspective on how our current crises of polarization and tribalism may be rooted in classic tunes like “Sweet Home Alabama,” “Fortunate Son,” or “Breaking the Law.” More broadly, Takin’ Care of Business is about how ephemeral commercial culture may have a greater resonance within society as a whole – more enduring, more meaningful, and sometimes more surprising – than we initially expect. It’s a topic I’ve explored in all my writing, and will continue to explore in the future. Thanks for reading, and watch this space.